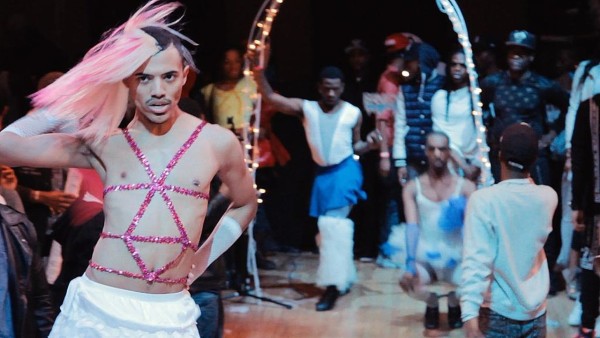

Courtesy of Story AB, Hard Working Movies, and Film Väst

Our final film review of the 2016 Inside Out LGBT Film Festival is Kiki (2016), a documentary by Swedish filmmaker Sara Jordenö and Twiggy Pucci Garcon about voguing in NY.

Let’s bitch it out…

It would be disingenuous to simply suggest that Kiki is about voguing – the film uses the dance style as a entry point to examine much larger issues with the black, trans LGBT community in NY. The film is populated by a variety of young men and women in their late teens to early twenties, many of them living lives affected by issues of homelessness, homophobia, illness, poverty and discrimination. The voguing contests bring the majority of the characters together; so do the Kiki houses to which they belong (these pass by in a blur early in the film, but contribute little to the narrative; what is important is how House Mothers and Fathers become responsible for the next generation, producing a web of support that eschews traditional notions of family in favour of a community that supports and protects its own).

Unfortunately Kiki is weighed down by the plethora of subjects it attempts to tackle in its brief 1 hour 40 minute run-time. A number of other reviews make comparisons to influential documentary Paris is Burning, which tackled a similar topic in the 1980s, but – full confession – I haven’t seen that documentary and shouldn’t need to in order for Kiki to work (audiences shouldn’t be required to be LGBT historians, even if we could benefit from it). The documentary provides some detail of the structure of the Kiki contests, as well as the historical grounding of the movement as an outlet for social activism and community building, but the specifics of how the system, lexicon and Houses work are barely sketched out and take a back seat in the middle and final acts. It’s here that Kiki both excels and disappoints: three characters (co-director Twiggy, his best friend Chi Chi Mizrahi and trans woman/activist Gia Marie Love) emerge as the main characters, but a variety of secondary characters are seemingly introduced solely to embody a relevant issue. For example: Zariya, a beautiful young trans woman gets only a few snippets to explain how her transition got her thrown out of her house and how she now survives as an escort to pay for costly hormone injections and surgeries. Zariya is fascinating, well-spoken and engaging, but we barely meet her before she recedes into the background.

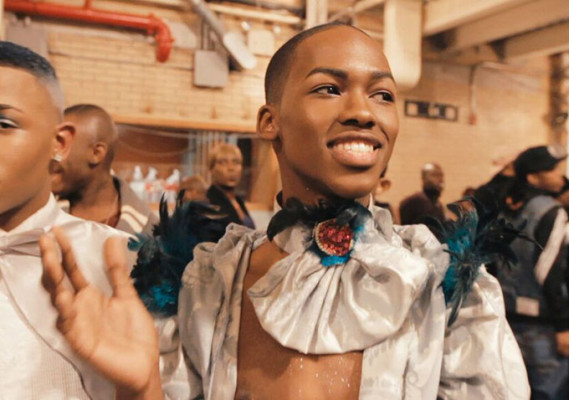

Courtesy of Story AB, Hard Working Movies, and Film Väst

These kinds of fascinating stories are at the heart of Kiki, but one is barely addressed before another half dozen are introduced. Police brutality, homophobic parents, and sex work are mixed in with eviction notices and challenges for trans women to find work, but there’s never time for an in-depth exploration. The issues drive the film, but there’s no conflict or climax to provide structure or resolution, and while this may be a deliberate attempt by director Jordenö to mirror the reality of these characters’ lives, it doesn’t ultimately satisfy. Rather than chuck in a bit of everything, Jordenö might have been more selective and delved deeper into the roots and complexities of these issues in order to give them the weight they deserve. This is particularly frustrating when it comes to issues of economics, as questions relating to jobs and rent subconsciously dominate the latter half of the film with aggravatingly few details provided.

There are also a few questionable aesthetic choices by Jordenö. Characters are not introduced with a title card so it becomes easy to misidentify them and their connections within the Houses (and to each other) are often unclear. Frequent voice-over narrated portraits of the characters facing the camera become tiresome and lose their impact, particularly when this technique is repeatedly employed late in the film. Finally, while the slow-motion sequences of Kiki solos on the stage of an empty theater equate the dance style with high art, they also introduce a bizarre sense of artificiality (Where are we? Who is paying for this theatre? Why is it empty?) and reinforces how little we know about what constitutes “good” and “bad” voguing.

Bottom Line: Kiki features a cast of eloquent, engaging characters struggling against a broad range of socio, economic, and political obstacles, but the way that filmmaker Jordenö engages with the context and history of these issues lacks depth. Ultimately there are enough fascinating characters and issues that Kiki might have been better served as a miniseries.

Kiki makes its Canadian debut Sunday, June 5 at 7:30pm at Inside Out.