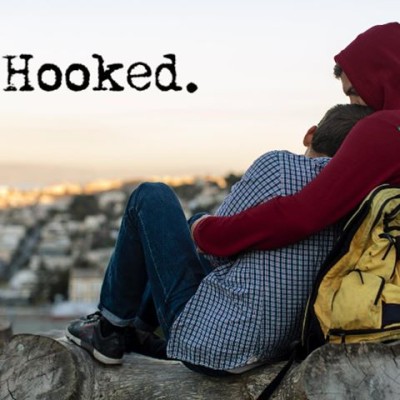

Our coverage of the 2017 Inside Out LGBT Film Festival starts on a clichéd note with Hooked.

Let’s bitch it out…

The vast majority of LGBT films are marked by specific themes: coming out stories, AIDS stories, drug stories and, occasionally, straight/gay love stories. For better or worse these are the stories that filmmakers have chosen to focus on when they’re telling queer stories, which can sometimes produce a sense of “been here, seen that” sameness for audiences.

Hooked is the debut feature of social media star Max Emerson, a YouTube and Instagram personality who is well known for his shirtless videos and pics. Making its World Premiere in a plum Saturday night slot at the Inside Out festival suggests that festival organizers are familiar with Emerson’s legion of followers (745K) and are seeking to capitalize on his popularity. To hear him discuss the film, Hooked is Emerson’s passion project; he is interested in raising awareness of LGBT homelessness, drug addiction and suicide (the coda even provides statistics and a link on how to get involved).

If raising social awareness of LGBT issues was Emerson’s aim, he lost sight of his goal during production. The problems are rooted in the film’s screenplay, which Emerson also wrote. Hooked begins as a grounded take on Jack (Conor Donally) and Tom (Sean Ormond), a pair of teenage lovers desperate to make ends meet in New York. Jack is the older of the pair and Tom arrives in the Big Apple to help his escort boyfriend celebrate his 18th birthday. Almost immediately, there are warning signs that a rocky road lies ahead. Jack has a mildly violent encounter with a German john that highlights both the dangers of the job and foreshadows bigger developments to come, the boys live with an angry homophobic roommate in a boarding house and the threat of underage Tom being forced by unsupportive parents to live with an uncle in Mexico City looms over the lovers. Hooked is at its best when it lives within the boy’s romantic “us vs the world” bubble, even if at times Emerson lays on their preciousness a little thick (a slow-motion montage of the boys assaulting random passerbys with their favourite condiments – ketchup and mustard – is both too long and not as amusing as Emerson believes).

The birthday antics introduce the film’s third main character, Ken (Terrance Murphy), an older married man unable to repress his inner same-sex urges. While there’s nothing wrong with Murphy’s performance, the character is the screenplay’s first major problematic element: Ken continually pulls focus away from Jack and Tom, leading the narrative astray with scenes involving his wife, new baby and in-laws. The dual story lines initially make it unclear who the protagonist is and whether the audience is meant to invest in Ken. His next encounter with Jack is the film’s turning point, but rather than coming together into a cohesive narrative, their date at a fancy restaurant plummets Hooked into ludicrous territory from which the film never recovers. An impromptu weekend vacation to Miami (proposed literally minutes into the date), Jack’s irrational belief that Ken will “save” him and Tom after knowing the man for less than a day and an all-too familiar descent into recreational drugs, creepy abusive men and Ken’s outing are all obvious and tedious.

Perhaps the predictable narrative would be more tolerable if Emerson was presenting a fresh perspective or offering us three dimensional characters to invest in, but Hooked lacks either the skill or the ambition to do so. The tired developments infer that the precarious financial situation of LGBT youth will inevitably lead to exploitation, prostitution, drug dependency and possibly murder and/or suicide. It is alarmist and simultaneously exploitative (it is difficult to take the film’s melodramatic elements seriously when Emerson lets his camera repeatedly linger on Donally’s toned, semi-naked body). Meanwhile, all humans, especially gay men, are presented as reprehensible creeps; the men that Jack meets in Miami only want to use him for his body or they’re just as messed up as him. Particularly strange is Emerson’s uniform presentation of johns as either violently abusive, fetishistic weirdos or both.

As the de facto protagonist, Jack is more than a little abrasive. He is prone to violence, juvenile behaviour and irrational decision-making and while character likability isn’t a deal-breaker for many films, it becomes increasingly difficult to sympathize with Jack or understand his motivations, especially in the third act. Even as the film tries to raise the stakes, it is never clear why Jack goes so destructively off the rails: he acts as though all is lost, but he has temporary lodging, a return plane ticket to New York and Tom is en route to be with him. Frustratingly, Jack’s casual admission that he’s bi-polar feels like one of the more authentic character beats, but the idea is dropped almost as soon as it is raised. Jack clearly has trust, impulse control and anger management issues, but Emerson is less interested in those than he is in mining drama out of lurid, sensational material. Rather than dig into the issues purportedly driving the film’s creation, Emerson leans into casual drug use, petty theft and dangerous johns (all filmed as a familiar swirling, hazy drug binge with uncomfortable suicidal visuals). This is aggravating because Emerson is simply retreading territory addressed in so many other LGBT films (only with a bigger Kickstarter budget).

The Bottom Line: It is clear after watching Hooked that Emerson needed a firm, guiding hand to help him craft his script. While he may have begun the project with noble intentions, the finished product is a disjointed mess of clichés that do not have much new or insightful to say about issues affecting homeless LGBT youth. Audiences looking for a polished looking project with requisite partial nudity and lurid melodrama will be content with the film, but unfortunately there isn’t a lot of new ground being broken in Emerson’s directorial debut.